Friday, November 22, 2013

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Life Moves On Very Fast

It's now the start of another semester but I can't yet return to ruminate about life in the university because I am simply assailed by quite a number of writing assignments and other things I need to do before the end of the year. After November came with the news of typhoon Yolanda, life simply moved on very fast I really had some trouble catching up. A day or two after Yolanda (international codename Haiyan), German journalist Martina Merten, who used to be my Health Journalism teacher at ADMU, emailed, asking for some news about the typhoon's impact in the Visayas because she said, they were only getting almost the "same kind of stories" in Germany. I wonder what she meant by the "same kind of stories" they were getting, and I never had the chance to ask her where in Germany was she reporting from. I merely provided her links to some coverage by journalists who actually covered the disaster because I was only here in Davao, and it took a long while before the stories from the typhoon's survivors came flowing in.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

The Saddam of Sitio Calinogan

Over a hundred people hid under this Saddam truck at the height of Supertyphoon Pablo (international codename Bopha) in this hinterland sitio Calinogan, barangay Casosoon in Monkayo town of Compostela Valley after the typhoon made its landfall in Baganga, Davao Oriental. I did not believe it at first: over a hundred people squeezed themselves together under this truck? I asked again after they told me. “Yes,” said one or two women, while the men nodded. “There were whole families there, children, women, everyone! We can’t find any stronger structure around, the wind was very strong, threatening to blow away our houses. Some of us who were near the cliff, squeezed our bodies against the cliff wall so that we won’t get blown by the wind,” said the villagers who have lived in the area for so long but had never experienced being buffeted by a typhoon.Pablo came upon this elevated sitio (how many thousand feet?) overlooking Nabunturan. The Dibabawuns live here for centuries. At five to six in the morning of December 4, 2012, they said, it was so dark (or white?), they could not see anything, they can only feel the very strong wind. I listened to their heart-breaking story of the storm: the houses that were blown away, the desperate search for food and water, the hand to mouth existence while they waited for their livelihood to recover.

When I saw the devastation of Tacloban in the aftermath of Supertyphoon Yolanda (international codename Haiyan), I remember this community and their Saddam truck. How long can our people recover now that we are being buffeted by typhoons and other disasters, year after year?

Monday, November 18, 2013

Remembering Doris Lessing

When I told them at the breakfast table the sad news that Doris Lessing has passed away, Sean suddenly looked up, asked me what it was that she wrote that he was familiar with? I started. “You? Familiar with Doris Lessing?” He said, yes, nodding his head. “She is very familiar, what was it that she wrote?”

So, I thought: What was it that she wrote that a 12-year-old must have heard? She wrote The Golden Notebook, which I did not finish reading, so, it wasn't very likely that a 12-year-old could be familiar with it; or Martha Quest, which I kept hidden among my books at home; or, was it, The Grass is Singing? But it was a woman's story, how could a boy be familiar with it? Or was it Under my Skin? which was an autobiography? Or, some of the African Stories? No, I never shared anything about Africa with him, I could not understand Africa so well; besides, there were a lot of strange names that he might have found funny when the stories were quite serious. “The Grass is Singing?” I asked. “No,” he said, “Something you kept talking about. Something you never could stop talking.” Aaaaaaah, I said, finally remembering. “Briefing for a Descent into Hell!”

The Story of Kialeg

Years ago, in the course of researching the town of Magsaysay for a Canadian-funded book project focused on Mindanao's five poorest towns, I came upon the story of Kialeg. He was a B'laan warrior-hero whose legendary exploits his people remembered well. I reveled at this discovery because I knew the old name of Magsaysay used to be Kialeg; and despite the government's attempt to replace the town's name with that of a Philippine president who died in a plane crash, people never stopped calling the place Kialeg. I thought that in a place like Magsaysay, the government may have imposed another history upon the people, but in the people's heart, Kialeg lives.

I could no longer remember whether I heard about what Kialeg did for his people that his name continued to stick. But a river running its course somewhere in town was also named after him. In fact, some town officials who never knew anything about Kialeg, the B'laan hero, thought that the old town was named after a river. But I had a discovery when I visited Pa's farm in Upper B'la last Sunday: The creek, we previously thought as dead because it was often dry most months of the year; the creek that cuts across Pa's piece of land, is actually Kialeg on his way downtown!

Nice meeting you, warrior hero!

Friday, November 08, 2013

Carried Away

Sometime in 1992, when I made a total mess of myself, I half-expected, even fervently wished, my family would bail me out from a monster called Fax Elorde. Of course, you could never expect such a thing so, I suffered the agony in silence. Mirisi. I did not say that to myself, though. I was still too young to understand I was in a real big trouble for life. I put up a brave face, invented stories, pretended everything was all right although Fax Elorde was a total asshole, so stuffy, so full of himself, so full of hot air. It’s only much, much later when his son would describe him as “just a practical guy, totally devoid of talent” that I enjoyed a hearty laugh; but at that time, I particularly wished I had a rich Uncle to kick him out the door, turn him upside down, cover his whole body with catshit, tell him to go to hell and get lost forever. I toiled from eight o’clock until midnight and walked the deserted street home, tense, anxious, worried and always went to bed totally exhausted.

Monday, November 04, 2013

Sunday, November 03, 2013

Some personal resolves

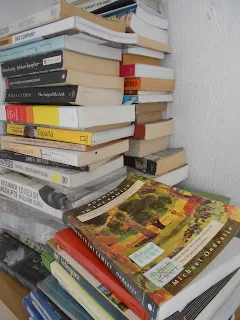

I have told myself I should clean up my room now that the semester is over. But first, I have this resolution to make: I promise to read the newspaper editorial every day, all the columns and the day’s banner headline, no matter what. Though, I don’t know how to do this without glancing at the growing book pile on the floor, on the top shelves, on the table. I really have to clear everything up. I made this promise the other day, but two days later, I already broke it. I was yanked out of my workplace and my daily routine by an emergency in my hometown—my mother in the hospital, whose daughter would not miss a column of a newspaper when a mother is sick?

Saturday, November 02, 2013

Lancelot By the River

Pa asked, "Why do you nurse such stupid dream of following a river? Of tracing where it came from, and then, following its path as it snakes around mountains, through ridges and ravines and meanders when it reaches the plains before it joins another river it meets along the way and form a bigger, stronger, and perhaps, noisier river, crisscrossing wide flat lands, sometimes, losing direction, forgetting its journey as it spreads itself too thin in some landscape and then, gathering momentum as it reaches some purposeful ravines that rushes onward towards the sea? Following rivers!" Pa exclaimed, "Isn't that a useless enterprise?"

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Jomgao's Salog

In Jomgao, people call the river “salog,” (sa-log), pronouncing saaa with a drawl before dropping fast the “log.” Saaaaalog, not salog, the Visayan word for floor, which you pronounce by dropping the two syllables very fast, one after the other. As a five-year-old arriving in my mother’s hometown for the first time, I was met by the sight of an enchanting white rock, partly covered by clinging green vines, hovering over the river. An older boy cousin, excited over our arrival, pointed to me the river, told me it was the saaaaa—log.

But I was enchanted by the white limestone rock hovering over it. I had never seen anything like it. It was a rock the color of old cathedrals. Its sheer beauty stuck to my mind, populated my dreams. Salog, for me was not the river but that white limestone rock hovering over it, a sight so enchanting, I could never, never get over it.

So, every time I go home to Jomgao and get lost on my way to the Aunts, I’d ask people where the salog was, hoping to recover my bearing. They would point the river—any river—to me. But no—I meant the salog, the real salog, that part of the river in Jomgao, where an enchanting white promontory hovered above, where I imagined Mangao and his wife Maria Cacao discreetly passing by on a stormy night, aboard an obscurely small boat full of chocolate bars.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Promises to be Broken

I promise to read the news first thing in the morning, I promise to read the editorials, the columns before everything else. I promise not to glance at the part of the room where my book pile is growing. I promise not to open the page of Van Gogh letters, where he described the scenes where he drew his paintings, I promise not to read nor open the pages of Hanif Kureishi nor of VS Naipaul nor Sheilfa's Flannery O'Connor. I promise to read NEWS only, nothing more. I promise to run everyday. I promise, I promise.

Semestral break, at last!

It's time for me to clear my desk of all the clutter, separate my reporter's notebooks from my journals; sort out the newspaper files, burn the documents I don't need, read the Granta, run, write and re-write my syllabus and come up with a whole new booklet; keep abreast with the breaking news, water the plants, mourn for the peppermint that died of neglect. Throw up.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Because my world is your world, too

I wrote my story on Maribojoc, Bohol in my mother's hospital bed. Nobody knew it. It was a very crammed ward, marked private, with only my mother and my father in it. I did it sitting on her bed, which was so small, I can hardly move my elbows. There was no electricity and no water when I arrived and it was very hot. My father sat forlornly on a bench across the bed."Were you pissed off, Pa, that your daughter took very long to arrive?" I asked, partly to strike a conversation and partly to ease my guilt. My father smiled. It took too long for me to come down because I could not extricate myself from my obligations. I was running out of cash and I knew how helpless I would be inside a hospital without cash. I was in panic as I interviewed people for my story, knowing that my mother was in the hospital, very sick. When the interviews were over, I brought the rest of my work to the hospital, trying very hard to summon all my energy to keep my mind in focus because the smell of dried sweat mingling with the smell of dust and medicine interfered. My sister arrived on a four o'clock bus from Butuan, asked me to meet her at the gate, but I was already fast asleep, I only read her message in the morning, when I awoke to find her talking to my mother, who was sick. I did not know how I finished my story. I sat there thinking about mothers and daughters and sisters and how they manage to survive.

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Argao, my real hometown

The rest were merely places where I was born, and where I grew up, or places where I spent the elementary years or high school years, maybe, college years or graduate school years; places where I saw the man with the guitar and totally lost my voice, or places where I fell in love with Jorge Luis Borges, or places where I learned to eat pan de coco while reading the Neo-Classicists, or places where I broke my heart inside an ancient building full of lost, ignorant souls; places where I fell in love with newborns, all my own; places where I struggled to earn my keeps, places where I cried over some happy movies, thinking of the laundry; places where I saw the shadow of Henry the VIII, King of England; places where I talked to a Caucasian named Angela, who kept shaking her head because of the really shocking gap between the rich and the poor in the Philippines, unlike in Africa where, she said, the gap was not that big because they were all poor; places where I heard about the unbearable news of the four girls gobbled up by mud and couldn't forgive myself for hearing it, places where I fell in love with a priest, places where I fell in love with a general, or places where I fell in love with a rebel; places where I worked and places where I used to sing inside a locked room so that no one can hear me; places where I danced alone. But all of them were merely places I passed by on my way to my hometown, where the Aunt talks about the names of strangers whose bones are carefully laid neatly inside the crypt.

Friday, October 18, 2013

Coins and Good Luck

Once, in one of our most precarious moments, Ja and I decided to take lunch at a carinderia whose food we deemed cheap, tasty and clean. I was about to take my seat when one of the five-peso coins I was holding sneakily fell out of my hands and silently crept into a corner. I heard its sound as it moved away. It was like a child complaining. It had some issues against me.

So I began searching for it inside that busy carinderia, attracting the attention of the sales staffs.

But the more I searched for it, the more it eluded me and the more that I needed it to court my luck. So, I did not give up. Instead, I relaxed and concentrated all my desire on finding it. Luckily enough, the coin appeared just when we were about to leave the place. It was just waiting for me to find it under the table.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Stranger

I can’t write because I’m bothered by a thought—a sad thought and a bad thought—and so, I spent the day re-reading Paul Theroux’s “The Stranger at the Palazzo D’Oro,” hoping to recover my focus. I was surprised because I already read the book before but I felt I was reading it for the first time. I remember nothing about the story except for its opening, where this young American student desired the life of a man he saw at a bar at an Italian Palazzo (a desire which had a way of coming true with the full impact of irony) and the scene where the narrator met the American student named Myra, on her way to Syracuse to see some paintings. But I felt strange because I used to recognize scenes I already read before but now, reading the book for the second time, I felt like I was plodding new territory. After I drifted off to sleep and awoke to finish the book, I read all my old New Yorker and did not move the whole day, so that when Ja and Sean arrived at dusk, seeing me sprawled on the floor with all the magazines, they asked why I was so depressed, I did not join them on the beach. Ja asked, too, if I wanted to sing again in a videoke but I said, no, I’d better stay home. “Are you really struck that hard, that you’re so devastated and depressed?” he asked. “Yes, of course,” I said and felt relieved. “I’m bleeding, can't you see?”

I really had a hard time dealing with it. “Why can’t you just put it aside and have fun?” Ja asked again.

I said, “Shhhhh.” Ja did not say a word. I kept telling myself I should not be sad. After all, Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize for Literature this year. I prefer her to Haruki. I needed to face my demons. I found pleasure in hunting for all those photography books I have accumulated through the years now languishing in abandoned corners of my room.

Wednesday, October 02, 2013

Friends and Fever

Cold compress—on his forehead, his neck, his armpits, his body. “Your friend, he met me at the canteen,” I told him, “He told me about you and then, another one came from another room, three or four of them, said you had such a fever, another one said you never ate anything for lunch, you must have already been very weak; and then, there were so many more; you had a battalion of friends so concerned about you, how come you are so popular?”

“Most of them are fakes!” he said, in between breaths, struggling to keep his eyes open, “You don’t even know some of them were bullying me. Plastic!"

"But they seemed so concerned."

"How come you don’t know a fake from the real?" he breathed and hissed. "They were only there for their curiosity. Just like Allied Bank, remember? The heist where there were so many dead and people came to see? They were there for almost the same purpose. They didn’t actually care about me! How come you can’t recognize a real friend from a fake?”

I was stomped.

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Maybe this is how they kill you

Please don’t send in anything that will crush me. I won’t be able to deal with it. I would die. I took the jeepney to Ecoland and went straight to the newsroom, bringing with me facts for stories. But I have trouble dealing with the facts of life. It’s a hard feeling. You feel the rock in your stomach. You feel the world come to a standstill. You keep seeing the faces of your boys: two pairs of lovely expectant eyes; wondering, waiting, you had to dig deep inside your soul for the last ounce of courage to tell them, wait a little while, son, it’s coming. But you know quite well it’s not. Nothing is coming. Not even Christ. Lesson learned: Never take documentation works anymore. It sounds easy but it’s not. It will take away your momentum to write; and it’s hard, janitorial work. I did it the past month and I haven’t gotten over it. They made me do it over and over again, so I had to set aside other jobs, I ended up not writing my stories, and now I face the prospect of not getting paid. It never happened to me before—to be made to repeat and rewrite over and over again—I feel dumb and stupid. I should not—should not do it again. I’m still reeling from shock. I can’t shake it off my system. I found myself watching, listening toBob, over and over again, until I was numb and dumb.

But I went home drunk with all of Dylan’s philosophy and all of Dylan’s music. Maybe, this is how they kill you. I got to be prepared.

Saturday, September 21, 2013

Game Over!

He used to say, the easiest to beat here at home is Dad; and the hardest to beat is Kuya Karl. I did not ask him what he thought about his Mother—is she easy to beat? I used to fake losing to him, closing my eyes or pretending to look the other way when his Bishop was about to capture my Queen. While waiting for his moves, stifling a yawn, I used to preoccupy myself with the characters on the chessboard. I used to say, “What are all your lazy pawns doing, leaving all your officers to do all the work? You better fire them.” Or, the "Bishops and Queen are so busy defending the King while all the pawns are sitting pretty." Sometimes, I’d say, “What’s that White Queen doing, flirting with my Black Bishop?” Then, I’d offer him some practical chessboard advice, “On the chessboard, as it is in Life, your best defense is offence. So, when you’re being attacked, don’t retreat. Relax, breathe deeply, and find an attack move to get out of the rut you are in.” But then, recently, I discovered I was straining myself more and more; and he is getting more and more pleasure toward the end games.

This morning, I discovered I was no longer pretending to lose. I was checkmated twice by his Rook and Queen, working together to trap my King.

The next time we will do it, I should target his Queen and Rook early in the game so that he will be crippled in the end game. Can he trap me with only two Bishops? I should target his Bishops, too. How about the Knight? Was that his Queen flirting with my Knight? Or, maybe, I should stop following all his Queen's salacious affairs and concentrate on the game, itself!

Reading Harper's

Harper’s threaten to dislodge The NewYorker as my favourite magazine. Drifting away from my usual course, I entered Victoria Plaza’s second floor Bookshop the other day and discovered an old Harper’s issue on its shelves, marked P20.00. When I opened the plastic-wrapped copy after I paid, the cover page immediately detached from its main body, and the pen scratches that I thought was only on its plastic cover, were actually scribbled on its cover, right on top of the caricature of William Finnegan’s title essay on the “Economics of Empire.” I threw the cashier a puzzled, and then, an accusatory look. The cashier pretended not to notice. Feeling very much cheated and duped, I was about to open my mouth to complain. But realizing that the cashier did not really valued or cared for what I valued, anyway, I decided to keep quiet.

At home, with the help of a scotch tape, scissors and all the love I could muster, I restored the old Harper’s back to its old glory and respectability. I still glanced with pain and grave irritation at the pen scribbling on its cover, but reading its pages, I began to delight on its highly-critical essays, which are ironic and iconoclastic at their best. But what I really appreciated were the artworks on its pages, announcing exhibits of certain artists on certain dates somewhere. I was particularly drawn by Keith Carter's art photo, “Conversation with an Owl,” and kept returning to it over and over again, marveling at the owl, a small object depicted in sharp focus, in contrast to the blurred figure of a man, crouching before it.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Monday, September 16, 2013

Eons ago, five months ago

On March 24, 2013, I had a very difficult time navigating my life. My table, as usual, was in a state of disarray. I could hardly touch anything. I was bothered by my pile of books gathering dust on top of that table. They included the upturned copy of Mark Twain’s "Letters from the Earth," which I promised to return back to Sheilfa’s pile at the Inquirer; "Soldedad’s Sister," which I reread again after an (almost) violent argument with Tyrone, who was furious that Butch Dalisay wrote about some disillusioned activist in his earlier book “Killing Time in a Warm Place,” when there were lots of activists who were not disillusioned; D’s copies of Paulynn Sicam’s "Heart and Mind" and Newsbreak’s "The Seven Deadly Deals," to read while we’re finishing our book, "State of Fear" and D was about to deliver a son; Lexa Rosean’s "Tarot Power," which served as my amulet against bad energy and souring friendships; Sheilfa’s Willa Cather’s "The Pioneer," on top of Ninotchka Rosca’s "State of War" on top of Ann Perry’s "The Street" on top of "The Joy of Yoga," which Prateesh and me bought in a bookstore somewhere near the SM North Edsa’s in 2009, the year Prateesh told me her Ma loved yoga but she could never take to it; DM Tomas' "Alexander Solzhenitsyn," someone's "Media Law," and "Stop the Killings in the Philippines" at the bottom. They were all gathering dust because I can’t touch them yet; I was still in the midst of Doris Lessing's "Briefing for a Descent into Hell" and Thomas Hardy’s biography written by his wife Florence, but which, University of Kent professor Michael Irwin said Thomas Hardy must have written himself.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Heartbroken

I keep posting nonsense here because the trip that would have brought me to see dear old Prateesh in Penang, Malaysia, got canceled and it really, really, really broke my heart.

The Beasts I Love

Danger once opened my eyes to the beauty of the horse in the mountains of Tudaya. Its body moving with mathematical precision against the precarious ravines, as if it had an intimate understanding of gravity, the force of nature that took centuries for scientists to understand.

Once, I also learned a lesson from the Bagobo horseman: "Allow the horse freedom to make decisions. The beast is familiar with the trail and knows what to do better than you do. Keep the rein just to keep it from jumping off the cliff but reining it in most of the time will limit its freedom of movement, impeding its progress, hence, you should really give the beast some leeway to get to where you are going." I love horses. I should find more time to spend along with them.

Old Jolly Good Fellows

Well. The one doing the tally said our group is getting to be male and older. Except for one (me) who happened to earn a master’s in journalism (only because of a scholarship targeting poor, indigent journalists from the Third World), almost everyone had courses other than journalism: there was an accountant, a civil engineer, a business administration graduate, a marine biologist. Most dabbled with radio and the local newspapers; the oldest, 65, Tatay Charlie, covers the Cotabato, Maguindanao and Sultan Kudarat area: fair, shiny white hair brushed off to one side, fairly elongated, slightly aquiline nose, fairly well-groomed and looking good despite the years, fond of wearing black, body hugging cotton shirt; the youngest, 26, could be Karlos, whom I have to nickname the wild, wild horse because he works for numerous media outlets at the same time, he’s still out in Vietnam, lugging his camera, just as he did when he waited on the path of the killer typhoon Pablo in December. So, he wasn’t around when the editors from Makati came. He couldn't make it to this bureau meeting, someone said, sayang, the food is flooding all over the place.

But if you talk about age, Frinston looked much younger because he, Frinston, is smaller; shorter than average and thin, too, which was more noticeable because of his skinhead; one Manila editor asked, what have we got here, are you still in the elementary school, boy? Frins mumbled something, rolled his eyes.

Some more bits of demographics: 13 men against three women. I wonder why women could not last in this kind of job? Cecille and Ayan used to be active for a while but they went somewhere else, to a much more financially-rewarding NGO work because this work could not make ends meet, they wanted more to be able to raise their children, have a decent life, a home and a car, maybe, a vacation in Europe, once in a while. Perhaps, they feel they don’t have time for ego-tripping. Which made me really feel very, very guilty for staying because—look at my boys, how are they, trying to survive in the mediocrity of their elementary years on their own because I don’t have enough money to pay for the private school tuition.

And yet, what a delight to be with the group.

Singing the Beegees' How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, all eyes on the lyrics of someone’s iphone: Dennis, the fair-looking guy holding the microphone, has become stouter, lumbering the past years; Rich, who came all the way from Iligan, slightly-stretched upper lip exuding an air of contentment; and Frinston, dancing to the tune, trying to catch up with the rhythm; while Mr. X, watched from a distance, listening, eyeing them. He’s a quiet, sober type of fellow and a disciplinarian, at that. Health-conscious, never smoke nor drink, he delights in his muscled arms and the strength and leanness of his body. He doesn’t overeat, unlike most of us; me, especially when I’m angry. I wondered if X already survived all the threats for his life. He narrowly escaped Ampatuan, I remember with a shudder. I don’t want to think about it, don’t want to mention it; no, not anymore. C, the tall guy wearing a cap, walking to and fro and around the singing trio, just arrived from Qatar, where he worked to earn more money than what he was getting as a correspondent. “It would suit you here, Day, because we’re writing fiction, here, it’s your genre, Day, creative writing, because there’s no freedom of the press here, so, we have to be creative,” he wrote to me, once, while still in Qatar. I was surprised to see him. When I arrived, he was already taking lunch, mumbling about his Indian editors and their Arab financiers; the Arabs, who got money, knew no English, so they leave everything to the Indians, who knew almost nothing about newspapering, but still felt in control because of their close friendship with the Arabs. “I don’t want to work with the Indians, Day, they think we, Filipinos, are their slaves.” I did not tell him I got dandruff and boils all over my body for thinking so hard for stories that will bring in the next pay.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

They don't mean to be rude, okay?

Maybe, nobody taught them manners here. One of them came up to me, asked if I had scheduled something for class that day because they have their exams for Media Law.

“Exams?!

I was surprised.

“But this is our class meeting. Your Media Law exams fall on our class hours?”

“No,” she corrected. “We’re having an exam tomorrow, that’s why we need to go home to study.”

“Ahh,” I said, nodding. “So, we won’t be having class today so you can finally go home and study for your other class' exams?”

Another one suddenly popped up on my Facebook to ask something about a systems analyst. I thought it had something to do with computers. She said something about journalists being systems analyst, and I said, haaah?

So, I asked, “Is this an assignment for your other class?”

“Yes, Ma’m. I was just a bit confused that’s why I decided to ask you, Ma’m.”

"Why don't you discuss that with your teacher?"

But worst of all, tonight. Shortly after I arrived in class, someone said, “Ma’m, we have to take shots of the candlelighting on the ground floor, it’s our assignment.”

It was already 6 pm, the start of our Wednesday class hour. “We have to go down to the activity level and photograph the candlelighting, Ma’m,” one of them said.

“What for?” I asked.

“We have an assignment for our Journ class, Ma’m.”

“So, you’re doing your assignment for the other class during my class?”

I looked at their faces, and get the sense, they didn’t really mean to be rude or insulting. Not at all. It's just that, they merely didn't know, they were already being rude and insulting. Who can blame them if they still had to learn their manners?

Monday, September 09, 2013

Memories of Kampung Ensika

Did anyone ever remember me in Sarawak? Did anyone ever think of me once in a while in the Iban Kampung of Ensika, where I once braved crossing the mighty Sadong Jaya river and another smaller river filled with crocodiles, to fall in love with a community of people, whose women so jolly and so warm, had guarded me against the terrible consequences of the tuak (pronounced tua) handed to me by their men. "Not too much, that's enough," I hear them whisper to each other in their own language, a language I could not understand, as the indigenous sweet wine was being poured into the glass. Their hands in a protective gesture, the look of genuine concern on their faces, those Malaysian women were enough to make me feel so safe and warm.

In contrast, a woman in a Christian household back in Kuching, wanted me to drown under her tuak, offering me glass after glass of it, I had a hard time refusing her. A tuak is a gesture of hospitality among the Ibans, refusing it was supposed to be considered rude; but remembering the Iban community whose women had protected me, I took the courage to refuse.

Now, I still think of those women, their brown faces smiling at me, saying things I don't understand, eternally amused by whatever I do in their village. Where could they be now? What could they be doing in the kampung, so far away from the city, accessible only by boat during high tide?

I may have forgotten their names, which were so strange and very difficult to pronounce, but I could not possibly forget their faces. Good memories of them I carry with me whereever I go.

Sunset at the Kuching Waterfront

Yes, that’s the Harbor View Hotel, when the sun’s last rays strike its rectangular shape before finally setting in the west to rest.

I used to watch the sunset here, while the crowd of people saunter into the waterfront, taking advantage of the evening breeze. I would be thinking of home, as I watch the light hit that side of the building, giving it a radiant glow before slowly fading away, and then, dying, dying in the onset of night. My heart would ache for Karl and Sean as strollers, teenagers and twenty-somethings pour into the waterfront, walking on the brick pathways under the trees.

I'd stay for a while, listening to their laughter, before walking around the street corner, where the Anglican Guest House, rises from a slopy, elevated ground, almost like the image of Christ after the resurrection. Curiously, the compound sits opposite the quaint Tua Pek Kong temple, whose smokes coming from numerous incense rise up to the heavens at all hours of the day.

I almost forgot the name of the guesthouse where I used to stay but here suddenly it pops up again--St. Thomas! Thanks, I remember you, St. Thomas Guesthouse, once my home inside the Anglican church compound just a few paces away from the waterfront. Once home for girls of a century-ago who studied there under the tutelage of the nuns. What happened to them afterwards? I remember climbing up the wooden stairway, my feet making creaking sounds at their every step. I could still see the shiny, wooden flooring, and the quaint smell of old sweat, body heat and old cigarettes. Ignoring the Caucasian backpackers, I would continue walking the dim interior of the bare living room and walk straight to my room. They still used this stick, skeletal old-fashioned keys which I had trouble inserting into the keyhole. I can still see the common baths and how it smelled of freshly-opened soap.

Why is it that sometimes, in my memory, I sense that I was not alone in that room? That somehow, Sean or Karl, or even Ja were actually with me? Why didn’t I ever get the sense that I was alone?

But I was alone in that room. I did not have a companion except for my thoughts and my cellphone. I would smell the dry odor of ancient cigarettes that refused to leave the linen no matter how many times those linens must have been washed. It was the Chinese professor in a university in Kajang, north of KL who told me about the place: very cheap, over a century year old wooden guesthouse full of ghosts from the previous century, rooms so tiny and homely, with sheets that smelled of old cigarettes. Surely, it would be within your budget. In the morning, I used to wake up to the strange calls of an Asian fowl, that resemble the chanting of monks somewhere in Bangkok.

Friday, September 06, 2013

Ah, Doris Lessing!

a photo grabbed from NewYorkTimes, October 11, 2007 issue.

So, what did the journalists do after they all crowded around you the day it was announced you won the Nobel Prize for Literature and Associated Press photographer Lefteris Pistarakis took this photo? Did you talk about Art and Literature? Did they ask you about Life? Or did they ask you about Art? Did you dismiss them all after you stood up from being slumped in your doorway like that, sitting on the steps, surprised and yet not surprised at all for winning the Nobel, after having been in the shortlist for about two decades? What else did they ask you? Did you return to them after you took the calls and the phone finally stopped ringing upstairs or did you just dismissed them right away just like how other people dismissed doves straying into their balconies? Did you invite them in for coffee, dinner or tea?

Mother may not have heard of you but in the different corners of her house, were strewn pieces of your writings, carefully wrapped in plastics to protect against the dust. Over the weekend, I found an old copy of Women&Fiction, and started reading your story, "To Room Nineteen," feeling all over again it was my story you were writing. Somewhere in some forgotten corners, your autobiography, "Under my Skin," and your other books, "The Golden Notebook," "The Grass is Singing" and several others, exist like some quiet creatures in an existential universe, waiting to be discovered. When I think about them, I think of this picture of yours, the day the announcement came. Slumped on your doorstep, reporters crowding around you, you showed what a writer ought to feel towards society's approval of ones art. You hardly cared at all. It was not the Nobel that propelled your writings.

That Old Letter

I could no longer find that goddamned letter. No matter how I tried or cried, I could no longer find it. The last time I saw it, I was either in that state university where I first saw you strumming the guitar, walking in from the rain, water droplets in your hair; or, maybe, I was home in B'la, and that letter was in a box. I said, the letter could never get lost here, the box was my only possession and I hid it from Mother, and since there was no place in the house that Mother could not see, I was secretly hoping that Mother would not open it. She should not because it was mine. The box contained the only things a girl could possess in the world, some notebooks and foolish writings, memorabilias from the barricade line and being such a small, humble, unassuming box, it was very easy to rummage, no letter could ever get lost there. So, I placed the letter in one of the pages of my old notebook, thinking I would go over it again and again, I will never get tired of reading it, especially when I was alone and Mother was not looking, and Nani, my cordon sanitaire, was not around, tucked away conveniently from my life. I said, I got to read that letter. I got to savor the feeling of being adored by those amazing pair of eyes and feel the blood tingling in my veins. It was not everyday that I felt my blood tingle. But I was still young and thin and lean and innocent and in love for the first time and too naive to know that the letter, being made of paper, could also get lost in a corner or get blown away by the wind as I was whisked away from there to places I've never been to; far away, very far away from you.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Identity Crisis

I like it when they call me Germelina. I happened to sit in the poet Allan Popa’s class, “Malikhaing Pagsulat,” in the summer of 2009 and I was not “Ma’med” there. I was with a bunch of undergraduate kids--they called me Germelina. When we had poetry readings, and they were whispering to each other whose poem was being read, the guy named Mike or Cedric or any such name, would tell his classmate, “That’s Germelina’s” and I felt like I was one of them, young again—am I fooling myself?

So, who is this woman they call Ma’m now? Sitting here at a table, with a wyteboard pen and eraser in her hand, pretending she had some intimate knowledge about the world?

What comes to mind was Reina, my editor, the second editor I ever had in my life, when I was still a young reporter and now, I’m not that young anymore, but still I remember that poet-writer-columnist the first beautiful real feminist I ever encountered. She used to tell us inside the newsroom, “Don’t call me, Ma’m, call me Reina,” and that’s how we called her Reina; though we were uncomfortable about it at first, because she was so ahead of us in years and intelligence, she deserved to be Ma’med.

But Reina was not that ordinary kind of Ma’m. She was fond of wearing shorts and thick glasses, and she had her Walkman always, the tiny wirings dangling down her ears somewhere, and once or twice, she jaywalked to cross the street to Sunstar office at Jones Avenue(this was in Cebu) without using the pedestrian lane and got caught by the traffic enforcers, whom she wrote about in her column the next day, praising them for doing such a good job of catching her. One time, as the story goes, the guard at the UP campus in Lahug, where she handled a journalism class, refused to let her in because she was wearing shorts and her usual T-shirt, complete with a Walkman, with the earphone on her ears, and those sunglasses. In her class, she also told her students, “Don’t call me, Ma’m, call me Reina,” but I heard she did not last very long there because the students petitioned her, they said she smoked in class and uttered expletives, which people were saying was okay at Diliman but not here in Cebu, it’s the province, the barrio, you see. I did not Ma’m Maritess, my first editor, the editor I can always claim to have taught me how to write a story. I did not Ma’m her because—well, she had a way of telling you something and you can't do anything else but obey and the first thing she told me, as I sat near her desk, where she edits her stories, was not to call her Ma'm—she was just three or four years ahead of me when I was still a reporter fresh out of school, entering a newsroom, feeling uncertain about the world.

Though Maritess deserved to be Ma’med every inch of the way: the way she imposed the editorial discipline, the way she taught me how to deal with sources, I owed it to her my beginnings in the newsroom. “Tell that source of yours, if she wanted a copy of your story, tell her to talk to the editor," she would say, with the usual pout in her mouth, her head tilted at an angle, "Or better tell her, we don’t do that in the newsroom, we have our editorial standards, but if you are really so desperate to read my story before publication, talk to the editor.” And I know some of them did not but some of those who did must have suffered such a lashing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)