Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Monday, September 16, 2013

Eons ago, five months ago

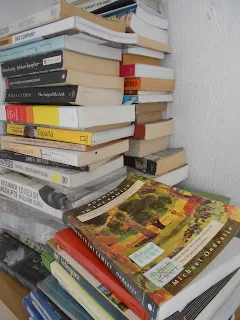

On March 24, 2013, I had a very difficult time navigating my life. My table, as usual, was in a state of disarray. I could hardly touch anything. I was bothered by my pile of books gathering dust on top of that table. They included the upturned copy of Mark Twain’s "Letters from the Earth," which I promised to return back to Sheilfa’s pile at the Inquirer; "Soldedad’s Sister," which I reread again after an (almost) violent argument with Tyrone, who was furious that Butch Dalisay wrote about some disillusioned activist in his earlier book “Killing Time in a Warm Place,” when there were lots of activists who were not disillusioned; D’s copies of Paulynn Sicam’s "Heart and Mind" and Newsbreak’s "The Seven Deadly Deals," to read while we’re finishing our book, "State of Fear" and D was about to deliver a son; Lexa Rosean’s "Tarot Power," which served as my amulet against bad energy and souring friendships; Sheilfa’s Willa Cather’s "The Pioneer," on top of Ninotchka Rosca’s "State of War" on top of Ann Perry’s "The Street" on top of "The Joy of Yoga," which Prateesh and me bought in a bookstore somewhere near the SM North Edsa’s in 2009, the year Prateesh told me her Ma loved yoga but she could never take to it; DM Tomas' "Alexander Solzhenitsyn," someone's "Media Law," and "Stop the Killings in the Philippines" at the bottom. They were all gathering dust because I can’t touch them yet; I was still in the midst of Doris Lessing's "Briefing for a Descent into Hell" and Thomas Hardy’s biography written by his wife Florence, but which, University of Kent professor Michael Irwin said Thomas Hardy must have written himself.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Heartbroken

I keep posting nonsense here because the trip that would have brought me to see dear old Prateesh in Penang, Malaysia, got canceled and it really, really, really broke my heart.

The Beasts I Love

Danger once opened my eyes to the beauty of the horse in the mountains of Tudaya. Its body moving with mathematical precision against the precarious ravines, as if it had an intimate understanding of gravity, the force of nature that took centuries for scientists to understand.

Once, I also learned a lesson from the Bagobo horseman: "Allow the horse freedom to make decisions. The beast is familiar with the trail and knows what to do better than you do. Keep the rein just to keep it from jumping off the cliff but reining it in most of the time will limit its freedom of movement, impeding its progress, hence, you should really give the beast some leeway to get to where you are going." I love horses. I should find more time to spend along with them.

Old Jolly Good Fellows

Well. The one doing the tally said our group is getting to be male and older. Except for one (me) who happened to earn a master’s in journalism (only because of a scholarship targeting poor, indigent journalists from the Third World), almost everyone had courses other than journalism: there was an accountant, a civil engineer, a business administration graduate, a marine biologist. Most dabbled with radio and the local newspapers; the oldest, 65, Tatay Charlie, covers the Cotabato, Maguindanao and Sultan Kudarat area: fair, shiny white hair brushed off to one side, fairly elongated, slightly aquiline nose, fairly well-groomed and looking good despite the years, fond of wearing black, body hugging cotton shirt; the youngest, 26, could be Karlos, whom I have to nickname the wild, wild horse because he works for numerous media outlets at the same time, he’s still out in Vietnam, lugging his camera, just as he did when he waited on the path of the killer typhoon Pablo in December. So, he wasn’t around when the editors from Makati came. He couldn't make it to this bureau meeting, someone said, sayang, the food is flooding all over the place.

But if you talk about age, Frinston looked much younger because he, Frinston, is smaller; shorter than average and thin, too, which was more noticeable because of his skinhead; one Manila editor asked, what have we got here, are you still in the elementary school, boy? Frins mumbled something, rolled his eyes.

Some more bits of demographics: 13 men against three women. I wonder why women could not last in this kind of job? Cecille and Ayan used to be active for a while but they went somewhere else, to a much more financially-rewarding NGO work because this work could not make ends meet, they wanted more to be able to raise their children, have a decent life, a home and a car, maybe, a vacation in Europe, once in a while. Perhaps, they feel they don’t have time for ego-tripping. Which made me really feel very, very guilty for staying because—look at my boys, how are they, trying to survive in the mediocrity of their elementary years on their own because I don’t have enough money to pay for the private school tuition.

And yet, what a delight to be with the group.

Singing the Beegees' How Can You Mend a Broken Heart, all eyes on the lyrics of someone’s iphone: Dennis, the fair-looking guy holding the microphone, has become stouter, lumbering the past years; Rich, who came all the way from Iligan, slightly-stretched upper lip exuding an air of contentment; and Frinston, dancing to the tune, trying to catch up with the rhythm; while Mr. X, watched from a distance, listening, eyeing them. He’s a quiet, sober type of fellow and a disciplinarian, at that. Health-conscious, never smoke nor drink, he delights in his muscled arms and the strength and leanness of his body. He doesn’t overeat, unlike most of us; me, especially when I’m angry. I wondered if X already survived all the threats for his life. He narrowly escaped Ampatuan, I remember with a shudder. I don’t want to think about it, don’t want to mention it; no, not anymore. C, the tall guy wearing a cap, walking to and fro and around the singing trio, just arrived from Qatar, where he worked to earn more money than what he was getting as a correspondent. “It would suit you here, Day, because we’re writing fiction, here, it’s your genre, Day, creative writing, because there’s no freedom of the press here, so, we have to be creative,” he wrote to me, once, while still in Qatar. I was surprised to see him. When I arrived, he was already taking lunch, mumbling about his Indian editors and their Arab financiers; the Arabs, who got money, knew no English, so they leave everything to the Indians, who knew almost nothing about newspapering, but still felt in control because of their close friendship with the Arabs. “I don’t want to work with the Indians, Day, they think we, Filipinos, are their slaves.” I did not tell him I got dandruff and boils all over my body for thinking so hard for stories that will bring in the next pay.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

They don't mean to be rude, okay?

Maybe, nobody taught them manners here. One of them came up to me, asked if I had scheduled something for class that day because they have their exams for Media Law.

“Exams?!

I was surprised.

“But this is our class meeting. Your Media Law exams fall on our class hours?”

“No,” she corrected. “We’re having an exam tomorrow, that’s why we need to go home to study.”

“Ahh,” I said, nodding. “So, we won’t be having class today so you can finally go home and study for your other class' exams?”

Another one suddenly popped up on my Facebook to ask something about a systems analyst. I thought it had something to do with computers. She said something about journalists being systems analyst, and I said, haaah?

So, I asked, “Is this an assignment for your other class?”

“Yes, Ma’m. I was just a bit confused that’s why I decided to ask you, Ma’m.”

"Why don't you discuss that with your teacher?"

But worst of all, tonight. Shortly after I arrived in class, someone said, “Ma’m, we have to take shots of the candlelighting on the ground floor, it’s our assignment.”

It was already 6 pm, the start of our Wednesday class hour. “We have to go down to the activity level and photograph the candlelighting, Ma’m,” one of them said.

“What for?” I asked.

“We have an assignment for our Journ class, Ma’m.”

“So, you’re doing your assignment for the other class during my class?”

I looked at their faces, and get the sense, they didn’t really mean to be rude or insulting. Not at all. It's just that, they merely didn't know, they were already being rude and insulting. Who can blame them if they still had to learn their manners?

Monday, September 09, 2013

Memories of Kampung Ensika

Did anyone ever remember me in Sarawak? Did anyone ever think of me once in a while in the Iban Kampung of Ensika, where I once braved crossing the mighty Sadong Jaya river and another smaller river filled with crocodiles, to fall in love with a community of people, whose women so jolly and so warm, had guarded me against the terrible consequences of the tuak (pronounced tua) handed to me by their men. "Not too much, that's enough," I hear them whisper to each other in their own language, a language I could not understand, as the indigenous sweet wine was being poured into the glass. Their hands in a protective gesture, the look of genuine concern on their faces, those Malaysian women were enough to make me feel so safe and warm.

In contrast, a woman in a Christian household back in Kuching, wanted me to drown under her tuak, offering me glass after glass of it, I had a hard time refusing her. A tuak is a gesture of hospitality among the Ibans, refusing it was supposed to be considered rude; but remembering the Iban community whose women had protected me, I took the courage to refuse.

Now, I still think of those women, their brown faces smiling at me, saying things I don't understand, eternally amused by whatever I do in their village. Where could they be now? What could they be doing in the kampung, so far away from the city, accessible only by boat during high tide?

I may have forgotten their names, which were so strange and very difficult to pronounce, but I could not possibly forget their faces. Good memories of them I carry with me whereever I go.

Sunset at the Kuching Waterfront

Yes, that’s the Harbor View Hotel, when the sun’s last rays strike its rectangular shape before finally setting in the west to rest.

I used to watch the sunset here, while the crowd of people saunter into the waterfront, taking advantage of the evening breeze. I would be thinking of home, as I watch the light hit that side of the building, giving it a radiant glow before slowly fading away, and then, dying, dying in the onset of night. My heart would ache for Karl and Sean as strollers, teenagers and twenty-somethings pour into the waterfront, walking on the brick pathways under the trees.

I'd stay for a while, listening to their laughter, before walking around the street corner, where the Anglican Guest House, rises from a slopy, elevated ground, almost like the image of Christ after the resurrection. Curiously, the compound sits opposite the quaint Tua Pek Kong temple, whose smokes coming from numerous incense rise up to the heavens at all hours of the day.

I almost forgot the name of the guesthouse where I used to stay but here suddenly it pops up again--St. Thomas! Thanks, I remember you, St. Thomas Guesthouse, once my home inside the Anglican church compound just a few paces away from the waterfront. Once home for girls of a century-ago who studied there under the tutelage of the nuns. What happened to them afterwards? I remember climbing up the wooden stairway, my feet making creaking sounds at their every step. I could still see the shiny, wooden flooring, and the quaint smell of old sweat, body heat and old cigarettes. Ignoring the Caucasian backpackers, I would continue walking the dim interior of the bare living room and walk straight to my room. They still used this stick, skeletal old-fashioned keys which I had trouble inserting into the keyhole. I can still see the common baths and how it smelled of freshly-opened soap.

Why is it that sometimes, in my memory, I sense that I was not alone in that room? That somehow, Sean or Karl, or even Ja were actually with me? Why didn’t I ever get the sense that I was alone?

But I was alone in that room. I did not have a companion except for my thoughts and my cellphone. I would smell the dry odor of ancient cigarettes that refused to leave the linen no matter how many times those linens must have been washed. It was the Chinese professor in a university in Kajang, north of KL who told me about the place: very cheap, over a century year old wooden guesthouse full of ghosts from the previous century, rooms so tiny and homely, with sheets that smelled of old cigarettes. Surely, it would be within your budget. In the morning, I used to wake up to the strange calls of an Asian fowl, that resemble the chanting of monks somewhere in Bangkok.

Friday, September 06, 2013

Ah, Doris Lessing!

a photo grabbed from NewYorkTimes, October 11, 2007 issue.

So, what did the journalists do after they all crowded around you the day it was announced you won the Nobel Prize for Literature and Associated Press photographer Lefteris Pistarakis took this photo? Did you talk about Art and Literature? Did they ask you about Life? Or did they ask you about Art? Did you dismiss them all after you stood up from being slumped in your doorway like that, sitting on the steps, surprised and yet not surprised at all for winning the Nobel, after having been in the shortlist for about two decades? What else did they ask you? Did you return to them after you took the calls and the phone finally stopped ringing upstairs or did you just dismissed them right away just like how other people dismissed doves straying into their balconies? Did you invite them in for coffee, dinner or tea?

Mother may not have heard of you but in the different corners of her house, were strewn pieces of your writings, carefully wrapped in plastics to protect against the dust. Over the weekend, I found an old copy of Women&Fiction, and started reading your story, "To Room Nineteen," feeling all over again it was my story you were writing. Somewhere in some forgotten corners, your autobiography, "Under my Skin," and your other books, "The Golden Notebook," "The Grass is Singing" and several others, exist like some quiet creatures in an existential universe, waiting to be discovered. When I think about them, I think of this picture of yours, the day the announcement came. Slumped on your doorstep, reporters crowding around you, you showed what a writer ought to feel towards society's approval of ones art. You hardly cared at all. It was not the Nobel that propelled your writings.

That Old Letter

I could no longer find that goddamned letter. No matter how I tried or cried, I could no longer find it. The last time I saw it, I was either in that state university where I first saw you strumming the guitar, walking in from the rain, water droplets in your hair; or, maybe, I was home in B'la, and that letter was in a box. I said, the letter could never get lost here, the box was my only possession and I hid it from Mother, and since there was no place in the house that Mother could not see, I was secretly hoping that Mother would not open it. She should not because it was mine. The box contained the only things a girl could possess in the world, some notebooks and foolish writings, memorabilias from the barricade line and being such a small, humble, unassuming box, it was very easy to rummage, no letter could ever get lost there. So, I placed the letter in one of the pages of my old notebook, thinking I would go over it again and again, I will never get tired of reading it, especially when I was alone and Mother was not looking, and Nani, my cordon sanitaire, was not around, tucked away conveniently from my life. I said, I got to read that letter. I got to savor the feeling of being adored by those amazing pair of eyes and feel the blood tingling in my veins. It was not everyday that I felt my blood tingle. But I was still young and thin and lean and innocent and in love for the first time and too naive to know that the letter, being made of paper, could also get lost in a corner or get blown away by the wind as I was whisked away from there to places I've never been to; far away, very far away from you.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Thursday, August 15, 2013

Identity Crisis

I like it when they call me Germelina. I happened to sit in the poet Allan Popa’s class, “Malikhaing Pagsulat,” in the summer of 2009 and I was not “Ma’med” there. I was with a bunch of undergraduate kids--they called me Germelina. When we had poetry readings, and they were whispering to each other whose poem was being read, the guy named Mike or Cedric or any such name, would tell his classmate, “That’s Germelina’s” and I felt like I was one of them, young again—am I fooling myself?

So, who is this woman they call Ma’m now? Sitting here at a table, with a wyteboard pen and eraser in her hand, pretending she had some intimate knowledge about the world?

What comes to mind was Reina, my editor, the second editor I ever had in my life, when I was still a young reporter and now, I’m not that young anymore, but still I remember that poet-writer-columnist the first beautiful real feminist I ever encountered. She used to tell us inside the newsroom, “Don’t call me, Ma’m, call me Reina,” and that’s how we called her Reina; though we were uncomfortable about it at first, because she was so ahead of us in years and intelligence, she deserved to be Ma’med.

But Reina was not that ordinary kind of Ma’m. She was fond of wearing shorts and thick glasses, and she had her Walkman always, the tiny wirings dangling down her ears somewhere, and once or twice, she jaywalked to cross the street to Sunstar office at Jones Avenue(this was in Cebu) without using the pedestrian lane and got caught by the traffic enforcers, whom she wrote about in her column the next day, praising them for doing such a good job of catching her. One time, as the story goes, the guard at the UP campus in Lahug, where she handled a journalism class, refused to let her in because she was wearing shorts and her usual T-shirt, complete with a Walkman, with the earphone on her ears, and those sunglasses. In her class, she also told her students, “Don’t call me, Ma’m, call me Reina,” but I heard she did not last very long there because the students petitioned her, they said she smoked in class and uttered expletives, which people were saying was okay at Diliman but not here in Cebu, it’s the province, the barrio, you see. I did not Ma’m Maritess, my first editor, the editor I can always claim to have taught me how to write a story. I did not Ma’m her because—well, she had a way of telling you something and you can't do anything else but obey and the first thing she told me, as I sat near her desk, where she edits her stories, was not to call her Ma'm—she was just three or four years ahead of me when I was still a reporter fresh out of school, entering a newsroom, feeling uncertain about the world.

Though Maritess deserved to be Ma’med every inch of the way: the way she imposed the editorial discipline, the way she taught me how to deal with sources, I owed it to her my beginnings in the newsroom. “Tell that source of yours, if she wanted a copy of your story, tell her to talk to the editor," she would say, with the usual pout in her mouth, her head tilted at an angle, "Or better tell her, we don’t do that in the newsroom, we have our editorial standards, but if you are really so desperate to read my story before publication, talk to the editor.” And I know some of them did not but some of those who did must have suffered such a lashing.

Monday, July 15, 2013

Reading Rebecca West

When things were becoming almost unbearable, I came upon Rebecca West's "The Fountain Overflows" tucked in a shelf under Karl's table. Paper-wrapped, and still inside the paper bag when I bought it, the book features a painting of a woman before a piano,and several other smaller paintings on its cover. I started reading, and immediately got immersed into another world: the world of Rose and her twin sister Mary, their sister Cordelia and baby brother Richard Quinn, their philandering no good of a father and the mother they love so much. At least, I forgot about my pain, if only for a moment.

Sunday, July 14, 2013

Blogs That Keep Me Whole

Sometimes when things turn totally insane and horrifying, I turn to blogs. Some people tend to dismiss blogs, but I find some deep sense of connection with these few blogs that I follow. At times, when things really go crazy, I turn to them to make sense of my world. I never mentioned this to anyone before. This used to be my best kept secret. But today, I honor these blogs for keeping me alive:

Daryll Jane's Free Migrant paints a turbulent inner landscape, something that I can identify with and freely enter; Prateesh's Room With a View is a refuge, Sheilfa's Tumbang Preso, another sanctuary fenced by sharp objects, Maryanne Moll's "Sensibilities," particularly her "My street, myself," or "I, watcher," a dream.

Sometimes, when I feel particularly sad and disturbed, I turn to Ma'm Merlie's poetry, and end up crying but no longer sad; and Ninotchka Rosca's Lily Pad, helps me get back my bearing; helps me think.

To all these writers and bloggers, thank you for writing what you write, thank you for making sense of the world.

Saturday, July 13, 2013

The Guy whose back was turned to me and Prateesh

Early in June, as soon as we stepped out of the cab inside the Ateneo campus, the puzzle was finally resolved. The man in robes, whose back we can see from the windows of the Rizal Library, where Prateesh and I used to look out, wondering and trying to figure out who the guy in robe was and never had enough time to find out until it was time for us to fly home, was actually St. Thomas More, the best friend of Henry VIII, who died in a guillotine upon Henry VIII's order.

Near the statue, an epitaph said something about Thomas More, a loyal friend to the King of England, but a more loyal servant to God.

I came upon Thomas More, not through the eyes of faith, I used to be an agnostic and now I am a pagan; but I came upon Thomas More's story through my depraved fascination of Henry VIII, the decadent monarch. Standing upon the grounds of Ateneo, carrying in my hands a box of Davao golden pomelos, which they said were the sweetest on earth, I realized how small a world it was, for Toto and I were going upstairs the social sciences building to see dr. V, Thomas More's memory right before me, and I wish Prateesh were there with me.

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

Monday, June 17, 2013

What am I doing here?

For two or three times now, at a particular hour at night, I have watched myself multiply four or five times before the wall as I took my descent from the fifth floor of this university building to the ground floor. I see the images of myself—five of them, of the same height and build—staring back at me, with a look that asked, “What are you doing here?” I did not know the answer. But the mirror on the wall seemed to be telling me what I certainly feel: I was only getting myself sliced; cut up to pieces.

The stairway looked dark and abandoned. Everybody still around at this time of night was rushing toward the elevator. Everything about the whole place looked squeaky and clean, which to one more accustomed to chaos like me, felt quite alienating.

If I had to work like this, would there be enough time for me to write? Would I even be able to talk about narrative techniques in a class still about to write a breaking story?

I was actually thinking of another university very close to the sea, whose turn-of-the-century campus was lined down by dark-limbed acacia trees, and the wooden buildings, particularly Katipunan Hall, looked like the exact place where Andres Bonifacio might just have held a meeting to overthrow the government of Spain. Was it Sheilfa, or was it Claire, who once said it was the only university that celebrated madness as a sign of genius, the madder you think there, the more accepted you get. Am I exaggerating? Is my own memory playing tricks on me, just like the mirrors on the stairway wall?

But from the windows of that university’s huge library, near the shelves and corners darkened with the languishing volumes of Balzac and Voltaire, I used to watch the green soccer field teeming with young athletes. I, too, considered myself mad, and remember that university with fondness.

In the place where I am now, they try hard to suppress madness. They ask you to dress well, to conform, to comb your hair, get a husband, make a happy home, such things. Sheilfa was mad, schizophrenic even, that’s why she’s really a good writer. Unlike me, she’s not afraid to offend. The greatest thing she ever brought to the office was a copy of Granta featuring an old rat. I loved reading about that rat, I can’t help crying at the end. Yet, Sheilfa was seized by sudden madness, and thought I found her anguish hilarious. She thought I was laughing at the sight of her hauling her delightful books near the office sofa. Perhaps, I was writing so badly, the meaning of my text spread beyond its original intention.

She never knew I lived the same life on the edges, and a delight offered by her books, made me last one more day.

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Monday, May 27, 2013

Friday, May 10, 2013

On the way to a Rainforest

We went to what I called the secret rainforest in Upper B'la, where the land sloped abruptly down to the Balawanan river about 100 to 200 feet below. I can't be exact about its height. Actually, I can't even tell a foot from a banana, so, don't trust me when I say 200 feet, maybe, it's even higher. But the cliff always had this effect of making me feel breathless as a child, both for its sheer height and for the landscape it offers. It had the same effect on me now.

When I was a child, I remember coming down here with my Pa, seeing the water falling by the steep slopes of the cliff, gushing like little waterfalls. I used to see gigantic bird's nest fern and other giant ferns as big as banana stalks thriving by the wayside. I remember the clear, rushing waters of the Balawanan, the pebbles the color of granite we used to play with. Now, the ferns were almost gone and the river was heavily silted, an island of rocks and debris had formed in the middle. But climbing down this place was such a great moment for me. The gigantic timber trees thriving near the rocky brook that ran its course through the ravines felt as solemn as a cathedral. I would love to come back here over and over again.

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Sickbed

It was a rare pleasure to have Sean read to me while I was sick. He would have refused but I said, "When you were a baby, you used to stop me and wrestle with me every time I read a book. So, now, it's your turn to please me. Just one page, please."

I closed my eyes and listened to the first paragraphs of Milan Kundera's "The Great Return," published by old Granta. First his voice sounded diffident, unsure. Then, he developed confidence and became daring as he gained paragraphs. My headache started to subside. Eventually, his eyes began to jump. "Voluntarily, not voluntary," I corrected.

He turned to me.

"How come you knew it was 'voluntarily,' not 'voluntary'?" he asked, "Your eyes were closed."

"I simply knew it," I said.

I was about to explain but quickly he cut me short.

"If you already knew everything, even with your eyes closed," he said, "Then, I don't have to read to you at all."

He put the book down and walked away.

Monday, March 25, 2013

Where is Sheilfa?

She vanished after Nico and I appeared lukewarm to her idea of turning the world upside down. The sight of her hauling all her books into the office used to make our day. I am still midway through her old Granta, its pages filled with her marks and comments, which really bothered me as I inched my way through Luc Sante's "Lingua Franca;" her copy of Marcel Proust's "In Search of Lost Time," conveniently gathering dust among the books on top of my cabinet which is not my bookstand, while I watch my dendrobium spikes new blooms right before my eyes, while I water my dillweed, my sage, my basil, my ailing oregano, and my peppermint forever attacked by wilt; while I cooked dishes in the kitchen and blackmailed Sean and Ja to tell me the food is good or else I might not cook again. Where is Sheilfa? She was the only woman who can speak what nobody else I knew dare to speak, with bitterness that could sting the eyes, with so much passion, with so much fury, with so much rage! Where is she?

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Admiring Elizabeth

About a year ago, I was at first intrigued, then, taken aback by the exciting and decadent life of Henry VIII, the English monarch father of the first Queen Elizabeth of England, as portrayed in The Tudors, the historical English drama fiction serialized in UK television created by Michael Hirst, filmed in Ireland, with Jonathan Rhys Meyers playing the character of King Henry VIII.

I was totally enthralled by the character that must have been Henry VIII, how charming and vain he was, how untrammelled in his sexual appetite, how irrational in his statesmanship and in his policy-making, I was willing to be taken in for a voyeuristic ride except for the disturbing scenes which I could not accept: the senseless slaughter of peasants who questioned and opposed Henry’s policies of shutting down and ransacking of abbeys in rural England, the untrammelled use of the torture machine inside the Tower of London to extract confessions from suspected heretics; the untiring and overzealous witch hunting carried to the height of abuses that led to the death of so many innocent people.

Yet, what really struck me was how accurately and astutely Henry VIII’s daughter Elizabeth figured out on her own how to survive as a woman in that patriarchal world: how rightfully and correctly she had guessed that her marrying someone, whether for love or for any other reason, will erode her power as a queen, and might even annihilate her as a person.

And so, Elizabeth, the astute Queen Elizabeth, deemed enemy and political rival of King Philip of Spain (the monarch in whose name tributes were extracted from the Philippines) lorded it all in England, ushering in the era of English history that brought about the likes of William Shakespeare.

But the reason I was struck by Elizabeth figuring out the equation of power all by herself, was because it took me years to understand that woman question myself, as it manifested itself in my life; and then, when I understood it completely, it was already too late. I could no longer do anything about it.

I admire Elizabeth for holding it out, for being so tough and strong, for keeping her emotions (and affection) in check and for keeping the men at bay while she stayed in power.

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Monument of Grief

January 14, 2013, the 40th day after the onslaught of the killer typhoon Pablo, a wall was unveiled in the old barangay site of Andap, New Bataan, bearing the name of those who died and those who went missing and were never found. Rampaging waters from the mountains reached a volume so high that it created a new river course, shortly after it passed the intersection of the Mayo and Mamada rivers, descending upon the whole barangay of Andap, washing away everything along the way.

Friday, January 11, 2013

Glossy M

At last, a lifestyle article! That's just how I feel when I write that story, "Coming Home: Teddy Casino's Davao." But I haven't got a copy of the magazine, yet; so, I haven't seen yet how the article came out.

River Crossing in Barangay Baugo

Tuesday, January 08, 2013

Bittersweet Stories

Soon the Task Force Mapalad book "Bittersweet Stories of Farm Workers in the Philippines, a project with Vera Files with Luz Rimban, Kira Paredes, Mylah Roque, and yours very truly, will soon be launched; and I personally dedicate my part to the farmworkers in the Philippines; especially those whose stories have not yet been told.

Friday, January 04, 2013

Nana Olang, Portrait of Old Sawata

How could I forget this old woman in the town of San Isidro, squatting in the doorway of an empty bodega whose wooden walls were darkening with age? I was on assignment for Newsbreak magazine sometime in 2007 when I realized I arrived in the village of Sawata-turned-San-Isidro-town too early for an interview. The town mayor just called me on the phone he would not be arriving in his office until past noontime that day, because he was still in some far flung fringes of the town doing something, a piece of news that practically sent me in a fit of panic and frustration. I was in a rush to get to the next towns of Asuncion and Kapalong to finish my assignments that day! Totally at a loss of what to do, I strayed towards an old bedraggled store, a few paces away from the townhall and noticed in a doorway of an empty bodega beside the store, an old woman squatting, as if lost to the world. For some reasons, I thought, the old woman could no longer talk to me. There was something about her that told me she was no longer there in that doorway; so, I befriended a middle-aged woman cooking bibingka by the roadside, eventually asking her the name of—and the permission to photograph—the old woman in the doorway. She said the name of the old woman was Nana Olang; and she can talk to answer my questions. I asked Nana Olang how it was when the village was still known as Sawata, how different or the same things were after the village was made into town?

I never knew that a woman like Nana Olang, who was then 72 at that time, could supply me with interesting nuggets of information I couldn’t get anywhere else (even if I happened to interview some venerable town officials that day). She described Sawata in the 1970s as "muddy" and "full of horse and carabao dung," where people from the surrounding mountain barangays came down to trade. She said it was already a far cry from how it was at the time when we met, because then, people from the city were already coming up the mountain barangays to buy farm goods at bargain prices. Nana Olang said she was glad that Sawata was turned into a town. When I took Nana Olang’s portrait, I never intended to submit it for publication. Yet, seized by a moment’s madness, I decided to send it to the magazine at the last moment as a portrait of life in San Isidro.

Just a few paces from where Nana Olang was, Nating Paras, 50, the middle-aged woman I first talked to, was cooking "bibingkang pinalutaw" (steamed rice cakes) right in front of a billiard hall near the roadside. She told me before she introduced me to Nana Olang she can't afford to buy a real bibingka-making "pugon" (oven), which cost at least P1,500.I still remember these small town assignments I did for Newsbreak with a certain degree of fondness. First, they took me away from the daily round of press conferences that was becoming a regular fare for news reporters every day; to travel off the beaten track to the lives of ordinary people. Most of these people never knew, or even read, Newsbreak itself; and it was often so vexing and exasperating to talk to officials of those small towns and tell them I was writing a story for Newsbreak, almost spelling N-E-W-S-B-R-E-A-K in bold, capital letters, to make them recognize what it was, a magazine priding itself as a must-read for the country’s top policy makers, in Congress and in the Senate in those days—and yet, the people I interviewed never had an inkling of what it was.

That day, when I strayed towards the bedraggled store, I did not have such pressures. I merely had the natural human feeling to talk to Nana Olang. I photographed her simply to remember her by. It never struck me at that time that such moments people normally regard as trivial could weigh so heavily, and with such meaning and significance, in the passage of time.

Thursday, January 03, 2013

Being Woman

I know she was not the one who posted all those things on her website because when I asked her for comment about something which was already posted there, her words were different. Well, she also meant the same thing, but the way she said it was different. No, I am not imagining things. I pointed it out to her just to let her know I still existed. I thought she overlooked my name when she sent those messages to everyone except me but the truth, I found out only now, was that she did not send anything to anybody. It was another person who sent them. The other person simply left me out; why can’t I get used to it? They’ve been used to doing things like this for centuries. The other person did not want to have anything to do with me, maybe, she hated me. Thinking about this, I feel depressed. I missed my laid back life in the state university when I was 17, and we used to gather together in groups to study Calculus. I can still see Alice, her longish face tilted, her doleful eyes drooping as she stops below the eaves of the Methodist Church’s Dormitory, turning to me, pausing dramatically just before the stairway to tell me, I had to be there at exactly six o’clock after prayer time because Rey or LaPaz will be there to help solve our problems.

As if Calculus, or Physics, or Chemistry, or even Spherical Trigonometry was even my problem. I was already uneasy then. But still, it took years for me to figure out what was the matter: that what was bogging me was not Calculus, nor Physics nor Chemistry nor Spherical Trigonometry, nor Engineering Mechanics. Not at all.

I remember staying inside the room of my dormitory, listening to the pitter-patter of rain outside the jalousie windows, watching the dewdrops on the leaves of grass, turning the pages of my book, and still, I failed to figure things out, failed to directly lay my finger on what really was bogging me. It took me half a century to figure out the problem. I never knew it then. The problem was being a woman.

Wednesday, January 02, 2013

Aunt's Fantastic Tale

EXCERPT FROM A JOURNAL. November 7, 2007.

Auntie Cora—Corazon Ignacio Lunas—arrived in this part of Mindanao I call B’la from Piddig (pronounced hard as Piddig), Ilocos Norte; a place about as far from Laoag city in Luzon as Bansalan is from Davao city here in Mindanao. (My Aunt wavered in her estimates here, quickly adding, as if to correct herself, “Maybe not Bansalan and Davao city, Day, but Bansalan and Santa Cruz town of Davao del Sur,” she said.)

She was still five years old when she arrived in B’la after the war. Everything was still a forest. She went to school in Grade One, in the first public school set up in B’la among the settlers. The neighbors were just a kilometre away, she recalled. Her classmates were already big, she said, “They were already bayongbayong,” she smiled, referring to boys approaching manhood, “and ulitawo (young men).”

When she reached Grade Three, she returned to Ilocos Norte and came back here at 22, to teach elementary school. Sometime in between, her father opened a kaingin in what is now known as Tagum city in Davao del Norte, the first settler to do so. Unfortunately, he was killed by a fallen tree, so, he was deprived of the fruits of his labor, my Aunt said.

The images she painted to me about B’la at that time bordered on the fantastic: Vegetables like squash, ampalaya and alugbati, just growing by the roadsides, with nobody planting them.

“They just grew wild abundantly in the forest,” my Aunt said. Everywhere in this part was still a forest, she said. Her Uncle Onor would set up a trap for deers and baboy ramo and when they heard an animal scream, they knew they had caught something. “What if they caught a man?” I asked, alarmed.

My Aunt is an Ilocana. She and Ma, who came from Argao, Cebu, are not in any way related except that they spent their whole lives teaching children in B’la (the mythical place where I grew up) and married the cousins from Mambusao, Capiz (my father and my uncle). My Aunt never had the chance to go back to Ilocos Norte since she married and had children (that’s how a place like B’la could tie someone down), so, when my Aunt had a chance for a brief visit up north in 2000, she was already having trouble with the language. She told me she felt she had lost her Ilocano tongue. Almost.

“I had to think first and construct my sentences before speaking,” my Aunt said. “The words no longer come out automatically to me like they used to.”

She said that because there are different variations of Ilocanos spoken in the north, there are already some words she could no longer understand.

Friday, December 21, 2012

The Wrath of Manurigao River

The wrath of the Manurigao River is turning into murky brown the color of the sea, I was about to say when I posted this picture. Seen from the highway of Caraga while on board Ramsey Ahmed's motorcycle about a week after typhoon Pablo, the vision itself looks threatening, reminding someone of a scene from Armageddon. Is that a natural color of the sea? I asked Ramsey, who stopped his skylab to allow me to take some pictures. The gigantic waves even dwarfed a carabao grazing under what remained standing of the coconuts along the shoreline. I have known Manurigao long before typhoon Pablo made its landfall in nearby Baganga and Cateel areas of Davao Oriental, leaving behind a trail of devastation to people and communities. Manurigao figured out in many of Allan Delideli's stories and anecdotes during the making of the book, "Understanding the Lumads: A Closer Look at a Misunderstood Culture." During those times, he couldn't help telling stories how the lumads had to hike for very long hours on their way to school, crossing the river along the way; and how dangerous the water current can get during days of torrential rainfall. When I arrived in that part of barangay Baugo, where the bridge traversing Manurigao had fallen, people told me how the logs had gathered its strength underneath the pillars supporting the bridge, so that eventually, the bridge had to give way. "It was also for good, Day," a storeowner said, "With all those logs gathered near the foot of the bridge, trapping the water, we would all have been submerged. If the bridge had stood, the water would have killed us all!"

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

Greenpeace comes to bring relief--and a warning

This story did not come out of the paper where I work, so, I decided to post it here. Greenpeace describes the recent typhoon Pablo as “very rare” and “unusual,” a sign that what has been predicted a decade ago about climate change is already happening.

Mark Dia, Greenpeace Southeast Asia typhoon Pablo operations chief, reiterated the environment watchdog’s warning for governments to do everything they can to stop carbon emissions, including calling off coal-fired power plants being lined up in Mindanao, before the worst can happen.

“It is very rare to see typhoons forming near the equator, especially at this time of the year. And for us (in the Philippines) to be hit by a category five typhoon is something unusual and extraordinary,” Dia said as the Greenpeace ship Esperanza docked at the berth 3 of Sasa wharf here, to deliver relief goods to typhoon victims.

He said the impact of the recent typhoon should be sufficient warning for the Philippine government to take with extreme urgency the call to shift away from coal-fired power plant in favour of renewable energy. “We have to act fast,” Dia said, “Are we going to wait for a tsunami type of event to happen?" he asked. "Even Japan has declared it will close a lot of its nuclear power plants after the Fukushima disaster.” “For those who are still skeptical, are we still going to risk more lives and limbs before you can change your mind?”

He cited the report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change that the severity of typhoons, drought and extreme weather conditions has been increasing in intensity for every rise in seawater temperature. “We don’t have any argument now that the weather has been changing in a very bad way,” he said, of the typhoon. He also said that for countries like the Philippines, identified among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change, with very limited resources to deal with the problem, “It is very urgent that we solve the problem, not only globally but also in our own small way,” he said.

“We have to ensure a better pathway for development, one of which should be a shift to from coal-fired power plants to renewable energy,” he said.

“If we will not help each other now, we can see more of this (typhoon) happening in the future and the cost will be immense in terms of property and agriculture and lives lost.”

He said once each coal-fired plant is built in the country, people will be stuck in this form of energy sources in the next 20-30 years, and hopes for the environment will be getting dim. “We have to do it now,” he said, referring to the shift to renewable energy. “We need to really act fast at the same time, start preparing for the worst.”

The Greenpeace ship Esperanza, which has last been involved in the clean up of the oil spill that hit the island of Guimaras several years back, unloaded 55 tons of relief goods from the Department of Social Welfare and Development and Save the Children Foundation to help the typhoon victims. “This is just a small thing against the immensity of the impact of the typhoon,” he said.

Friday, December 07, 2012

What Pablo brings in Compostela

December 6, 2012. Ja said as soon as I arrived several hours after dark, "How can you help yourself from being overwhelmed? Were you not overwhelmed? I've done that before and I was just overwhelmed. There were just so many things to shoot. Many things were happening all at once. You get distracted. You don't know where to start. You would naturally lose your focus. Even the most professional of of us, do, did you not lose your focus?" I said, "!!!"

He did expect me to lose focus. I felt bad because I ran out of battery. I showed him the pictures because I felt bad. 'Ahhh!" he said, "So, you lost focus, too! You're simply overwhelmed!"

I felt worse. I no longer wanted to see the rest of the pictures.

Earlier, at the Compostela terminal, I texted him, I'm going home now because I ran out of lithium. Instead of staying close to my subject whose houses were torn down, I allowed my subject to guide me to a bridge somewhere because they said that bridge directly face the valley of New Bataan, where many people were carried away by the flash flood. They said it was important that I should see that bridge across the Agusan River, which overflows sometimes, and inundate the landscape with muddy water. Perhaps, Ja was right. I was also overwhelmed. I let my subjects guide me, instead of me, charting the story. When we returned to their shattered hut, their Grandma was sitting on the old sofa in the midst of the muddy sala. She sat just below her picture on the wall, the last thing staying there after Pablo's devastation. The Grandma wearing the same dress as the one in the picture. I told her to stay where she was but when I finally pressed the shutter, my camera said, re-charge the battery!

The whole area had no electricity. I said I had to rush home. At the bus terminal, it was so hot I wanted to collapse. Somebody was selling water inside the old bus. He handed me one. It was warm. "Please give me a cold one," I said.

The vendor looked at me, then he looked around, then back at me. He said, tongue in cheek, "There's no brownout in this town," he said, glancing at the other passengers. "Yes, there's no brownout in this town," he said. "There's electricity everywhere."

Monday, November 26, 2012

Will you please tell Leopoldo I'm going back to Silliman U

Yes, we’ll go back to Dumaguete; yes, we will, we really will. Though, I have to warn you, this is beginning to sound like John Steinbeck’s alfalfa in Mice and Men—of Lenny and the rest dreaming of planting alfalfa on the patch of ground they dreamt of owning one day and never did, as far as that novel was concerned. We will still go back to Dumaguete—Karl, Sean and I; we’d get inside Silliman University as a matter of course; careful not to sit on the bench under the acacia no matter how tempting, because the itchy til-as is sure to fall from one of the branches, just like what it did to Karl the first time we arrived several years ago. Instead, we’d go straight to Katipunan Hall hoping to find Prof. Philip van Peele, the Belgian professor who speaks perfect Bisaya when all the rest of the teachers (Filipinos) speak English; perhaps, to ask him why some people like me have poor memories of sound?

Though, I am merely speaking from memory, I still would like to discover again how it was to walk the lane from the pier straight to the university, how it was to see for the first time the waves smashing violently against the seawall, as if the whole sight was a copy of an old painting; or, how it is to look up and listen to Karl’s six-year-old footfalls shaking the very foundation of the wooden Hibbard Hall; or was it the second floor of Katipunan, where the dean finally approved of all the subjects I was to take that semester? How could an unlettered soul like me arrive upon the shores of Silliman, dragging along with me a six-year-old child ripe for the first grade while I joined the graduate class at the English department just a spitting distance away? Soon, everybody I knew in Silliman was gone, except for the creative writer Ian Casocot and the venerable Cesar Aquino, every poet (including Sheilfa) calls “Sawi.” But still we find ourselves going back to Silliman, our thoughts straying inside Katipunan Hall, the domain of the English Department, a place which I described that first time I arrived as the most likely place where Andres Bonifacio could have held a meeting. But having exhausted our memories there, we’d go to Claytown to find out about the old apartment where Karl and I spent horribly lonely days together, our door switched in between the one occupied by an Indian couple and their five-year-old girl named Unnam (the Indian word for moon) and the door occupied by the Balikbayans who just arrived fresh from the US. We will find the spot where Rafael, Karl’s first pet kitten, died. One of the days-old kittens Karl’s Korean friends stole from the cat-mother, Rafael did not survive on milk and water. We will stand on the exact spot to remember the sadness written there, leaving a permanent mark in our hearts. If Silliman wouldn’t want me, I would be going there as a ghost. It would still be 5:30 pm of a typical university day, and I’d be rushing to Dr. Ceres Pioquinto’s Asian Literature class, trying to stop the ticking of time as I wait for a photocopy of Ceres’ lecture, while students ambled around me, whispering about my old alcatel; while I—hunched, waiting before the photocopying machine, praying hard I won’t be late, I won’t be late for Ceres’ class, fearing Ceres’ catastrophic outburst, which I used to find so devastating. Or, maybe, finding myself in that bookshop tucked somewhere beyond the public market, looking for some undiscovered English author but finding out to my dismay that the bookshop has already been mined of its best titles; all I found were rejects and leftovers. What do you expect? The whole university was crawling with scholars, writers and aspiring writers, potential artists, beating each other to such stuffs, while I was in my room at the Nerisse Dorm, trying to understand Plato’s Metaphysics before plodding on to the neo-classical poets.

Sheilfa said there was definitely one place inside the university we would not feel so outcast: inside the three-story library whose vast windows faced the expanse of the football field. We will go back to Silliman U and spend entire days inside the Library, hungry eyes mining the darkened rows of books displaying Balzac, Petrarch and the like. The last time I checked, I could no longer find Susan Sontag on the shelves. Her books were stolen. It was still the turn of the century. Year 2000. The air between the darkening rows of books written by Dead Authors was musty and full of mysteries.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Reading Miguel

Last night, while forcing myself to fart, I finished Miguel Syjuco’s “Ilustrado,” and in the morning, forcing myself to burp, I was still puzzling over its ending, I decided to read it again; discovering and deeply appreciating with utter amazement the book’s extraordinary style: Miguel Syjuco turning out to be fictional at the end of the novel; and Crispin Salvador, who was supposed to be dead at the beginning of the novel, turned out to be the one writing it—or do you get that disrupted feeling it is the other way around? Just to get a taste of how post-post-postmodern authors disrupt our usual order of reality, read the prologue and epilogue of the novel, written by Miguel Syjuco and Crispin Salvador, respectively, in route to Manila on December 1, 2002; and let's see if you won't get confused, or wouldn't want to take a pause and think; or, read the entire novel again, slowly, as in s-l-o-w-l-y so as not to suffer indigestion, in checking and counter-checking which reality you are still treading. This might be a good example of how the novel invents and re-invents. "Which point-of-view was it written?" Ja asked, over breakfast, as if the novel was written in the 1960s. No, not a point of view here, Ja, but points-of-view; and be careful when you speak, from which point of view are you speaking; because realities could easily be interchanged; the author playing, Miguel becoming Crispin and Cripin, becoming Miguel. It was a totally enervating experience!

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)